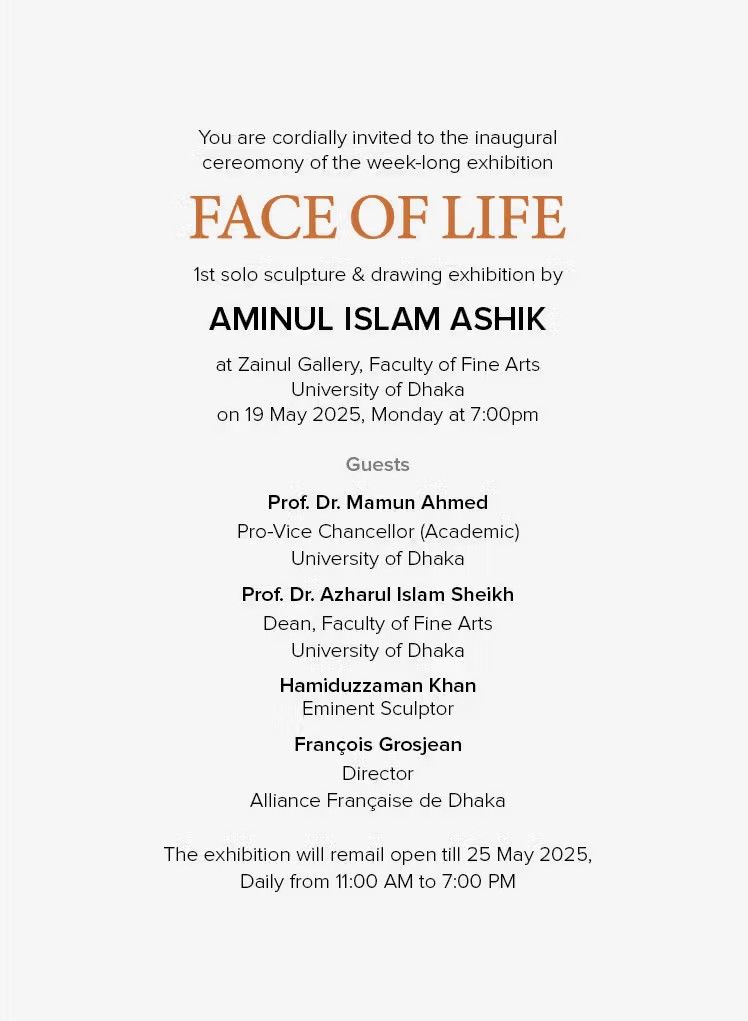

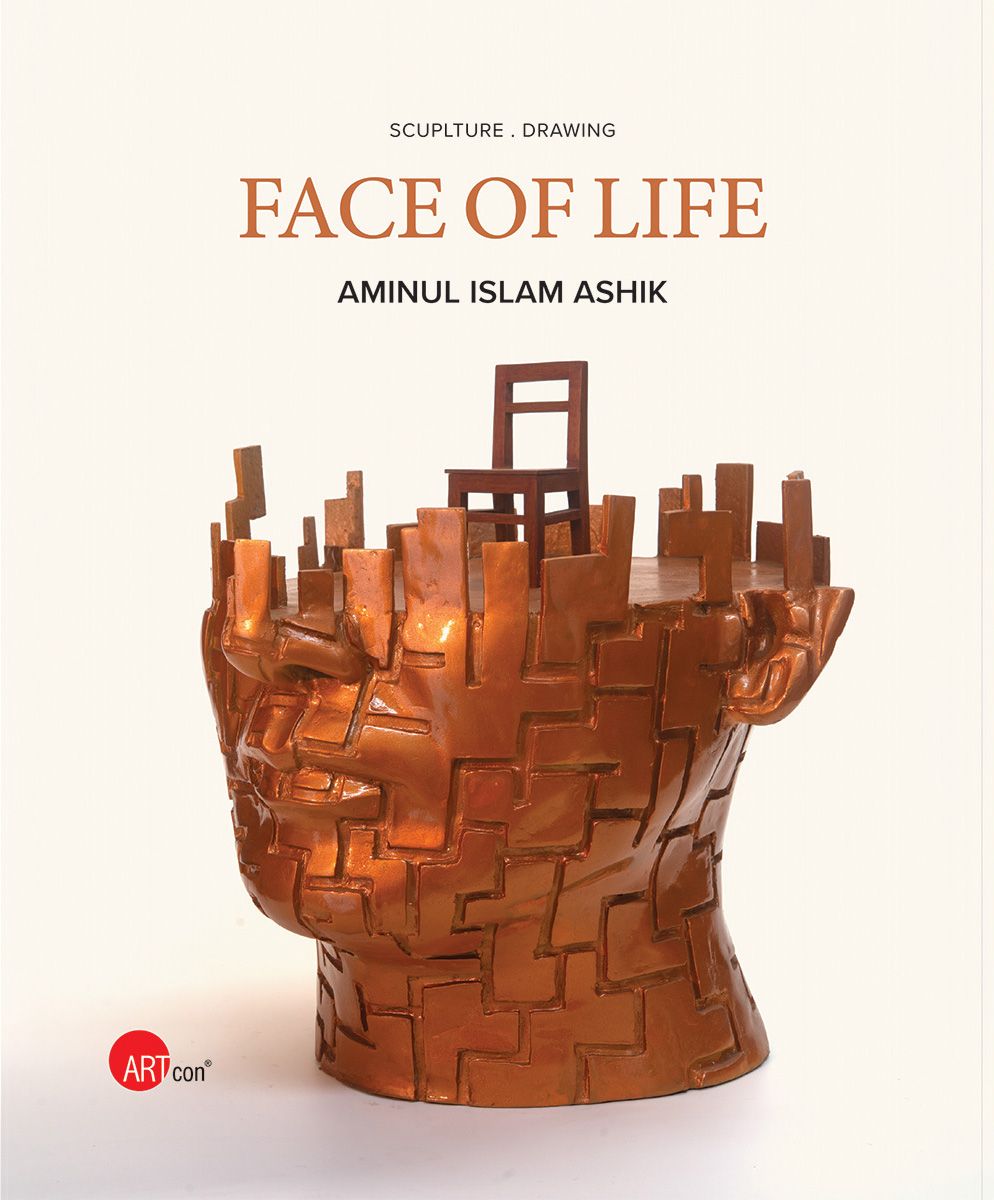

'FACE OF LIFE' showcases the powerful sculptural and conceptual practice of Aminul Islam Ashik, one of Bangladesh’s most provocative contemporary visual artists. Anchored in the symbolism of the human face and the metaphor of the “seat,” Ashik’s work explores emotional depth, societal conflict, and political power. This is his first solo exhibition, FACE OF LIFE, at Zainul Gallery, University of Dhaka, and features over 40 sculptures, drawings, and installations created between 2010 and 2025. Through materials like fibreglass, bronze, iron, and wood, Ashik confronts the fragile balance between resilience and vulnerability, personal identity and collective memory. His artistic voice—blending surrealism, political critique, and postmodern expression—offers a profound meditation on existence, power structures, and humanity’s place in nature. FACE OF LIFE is a philosophical journey into the art and mind of a transformative sculptor.

S C U L P T U R E . D R A W I N G

FACE OF LIFE

Aminul Islam Ashik

"Ashik’s art is rooted in the philosophical tension between humanity’s place within and against nature. This duality extends into social and political realms, where power and identity collide in cycles of struggle and adaptation."

Aminul Islam Ashik (b. 1988, Dhaka, Bangladesh) is a visual artist whose work navigates the emotional, political, and cognitive dimensions of human experience. A graduate of the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka (BFA 2010, MFA 2012), Ashik explores the human face as a symbolic medium—capturing moments of conflict, resilience, sorrow, and transformation. His practice spans sculpture, installation, and conceptual forms, often merging classical techniques with contemporary perspectives. Ashik’s art is rooted in the philosophical tension between humanity’s place within and against nature. This duality extends into social and political realms, where power and identity collide in cycles of struggle and adaptation. His works—ranging from portraits and objects to performative gestures—reflect layered realities shaped by both internal emotion and external forces. He has exhibited widely in Bangladesh and internationally, including at Documenta Fifteen (Germany), Kunsthaus Zürich (Switzerland), India Art Fair, Diriyah Biennale (Saudi Arabia), and Central Museum Utrecht (Netherlands). He has been an active participant in the Asian Art Biennale, National Art Exhibition, and collaborative projects with Britto—Arts Trust. Ashik’s works are in major public and private collections, including the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy and Liberation War Museum. He has received awards such as the Best Sculpture Award (18th Young Artists Exhibition) and Honorable Mention (24th National Art Exhibition), underscoring his evolving and reflective artistic journey.

In the Face of Life

My work explores the sensory and cognitive dimensions of the human experience, focusing on the face as a site of emotional and existential transformation. Through expressions shaped by happiness, sorrow, conflict, and change, I aim to depict the shifting nature of inner and outer human states. The face becomes a medium through which different organs and emotions surface at different moments, symbolizing the complex landscape of our being. Humanity exists within nature but is often at odds with it. Although human power is minimal compared to nature’s vastness, we continuously struggle—for survival, for recognition, for dominance. This struggle extends beyond nature and into our relationships: between people, families, communities, and nations. At the root of much global unrest lies a desire to claim influence, power, or position—an assertion of existence in the world. Power, in many cases, is pursued out of greed. While sacrifice is a more meaningful path to growth and significance, political structures often prioritise control over contribution. Whether in personal, social, or international contexts, the seat of power becomes symbolic—a place of status rather than purpose. Through my art, I examine these dynamics. I create symbolic portraits, conceptual compositions, and object-based installations to express political tension and personal ambition. At times, I draw parallels to classical artworks, reinterpreting their forms and messages to reflect today’s political realities. The Imagine series was born from these reflections—deeply inspired by the timeless message of John Lennon’s song Imagine. His vision of a world without borders, greed, or divisions resonates with my artistic pursuit: to visualise the shared emotional states and power struggles that define the human condition, while imagining a more unified and peaceful existence. My creative process is shaped by ongoing learning from people, society, and nature. I often re-evaluate past understandings as I evolve. For me, art is not static—it is a living process, a reflection of nature’s flow, ever-changing and continuous. Aminul Islam Ashik Visual Artist

FACE OF LIFE is a compelling art book showcasing the powerful sculptural and conceptual practice of Aminul Islam Ashik, one of Bangladesh’s most provocative contemporary visual artists. Anchored in the symbolism of the human face and the metaphor of the “seat,” Ashik’s work explores emotional depth, societal conflict, and political power. This monograph accompanies his first solo exhibition, FACE OF LIFE, at Zainul Gallery, University of Dhaka, and features over 40 sculptures, drawings, and installations created between 2010 and 2025. Through materials like fiberglass, bronze, iron, and wood, Ashik confronts the fragile balance between resilience and vulnerability, personal identity and collective memory. His artistic voice—blending surrealism, political critique, and postmodern expression—offers a profound meditation on existence, power structures, and humanity’s place in nature. With essays, curatorial notes, and rare studio insights, FACE OF LIFE is both a visual archive and a philosophical journey into the art and mind of a transformative sculptor.

"These works are not merely objects of form—they reflect Ashik’s inquiry into power, control, displacement, and identity."

Curatorial Note

ARK Reepon

It is an immense privilege to present 'Face of Life', the first solo exhibition and publication by Aminul Islam Ashik-a visual artist whose practice traverses the fragile boundaries of human emotion, existential conflict, and political symbolism. Over the past fifteen years, Ashik has developed a strikingly original voice in sculpture and conceptual art, and Face of Life gathers more than 40 of his various works into one resonant collection.

Ashik's sculptures and installations are not just objects-they are dialogues. With materials like fiberglass, iron, and wood, he excavates the psychological terrain of the human face and the symbolic weight of "the seat," which recurs as a metaphor for authority, identity, and vulnerability. His works compel us to reflect, not only on the visible face but on the inner fractures of our time-greed, displacement, survival, and the burden of recognition.

The exhibition takes its name from one of his key series, in which the face becomes a landscape of memory, resistance, and renewal. Ashik's works transcend language and geography, urging viewers to reconsider systems of power through deeply personal yet universally charged forms.

As ARTCON continues its mission to promote transformative contemporary art, we are proud to support this landmark moment in Ashik's journey. His ability to merge visual poetry with social critique makes his art a force of both reflection and resistance.

'Face of Life' is more than a showcase-it is a mirror to the forces that shape us and a call to see beyond what is visible. In Ashik's world, art does not conclude; it breathes, questions, and evolves.

We are honored to share his vision with the world.

"By extending his interest across society to understand power and polity, he attends to humans trapped in routinized existence. He dissects world leaders to show their volatile position in a world in transition."

Ashik’s Shiny Banal People

Mustafa Zaman

1.

Sculptor Aminul Islam Ashik conceives of art from a processual point of view – he sees it as a ‘living process’, to use his own words. His works testify to his commitment to a set of existential concerns – all of which are produced while he acts in time. For him, to ‘be in, or becoming within time’ boils down to the ‘here and now’, which he translates with the audacity of a postmodernist, making his protagonists look like props as though they are unknowingly living a life that at best can as best be defined as ‘banal’.

By extending his interest across society to understand power and polity, he attends to humans trapped in routinized existence. He dissects world leaders to show their volatile position in a world in transition. The artist’s intention to address issues of global dimension is clearly legible in his idioms, or should one say idioms, as Ashik keeps moving from one language to another, straddling the line between modernist form-specificity and postmodernist intention to break away from the mould of linguistic authenticity.

The postmodern pastiche appears in many pieces to emphasize the meaninglessness of existence. His works showcasing garishly coloured dancing figures are a case in point. They are reminiscent of Chinese postmodernists who masterfully bring to life the ‘fakery’ of collectivized life.

2.

To return to the idea of processual art, the cognitive as well as material processes through which the end results are determined in Ashik’s domain leave no space for any doubt about his intention to throw light on a world that has gone awry. In a country where artists reside in a box of ideas linked to romanticized race and language, he chooses to take a stab at ‘impersonal truth’. Accordingly, he makes sculptural pieces that intentionally snub the modernist aesthetic gambit of creating objects of poetic intention by letting the medium be expressive. Ashik takes a 360-degree turn and deliberately pushes the envelope so that the borders between commercial products and art simply fall away to make room for his processes to take the form of sculptural pieces. This also segues nicely with his other deconstructive processes – dissecting heads and placing familiar small-scale furniture between the two halves.

To deal with the human condition, which is an expressed intention of this young sculptor, the political-social concepts about the world order is made to collide with the ‘spiritual void’ that has been created by modern, profit-centric, technologized life. Hence, the facelessness of the faces and the pleasurelessness of the rejoicing people only mirror the banality of global leadership, as a handful of people are thoughtlessly making decisions for the millions to lead the world to ‘nowhere’.

Author is an Artist and Critic and Director of the Fine Art Department, Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy

"Ashik’s artistic style involves mastery in modeling physical form while emphasizing the process as a vehicle for personal expression. Although primarily a sculptor, Ashik feels comfortable experimenting across different mediums and processes."

Sculpting Through Silence

Mahbubur Rahman

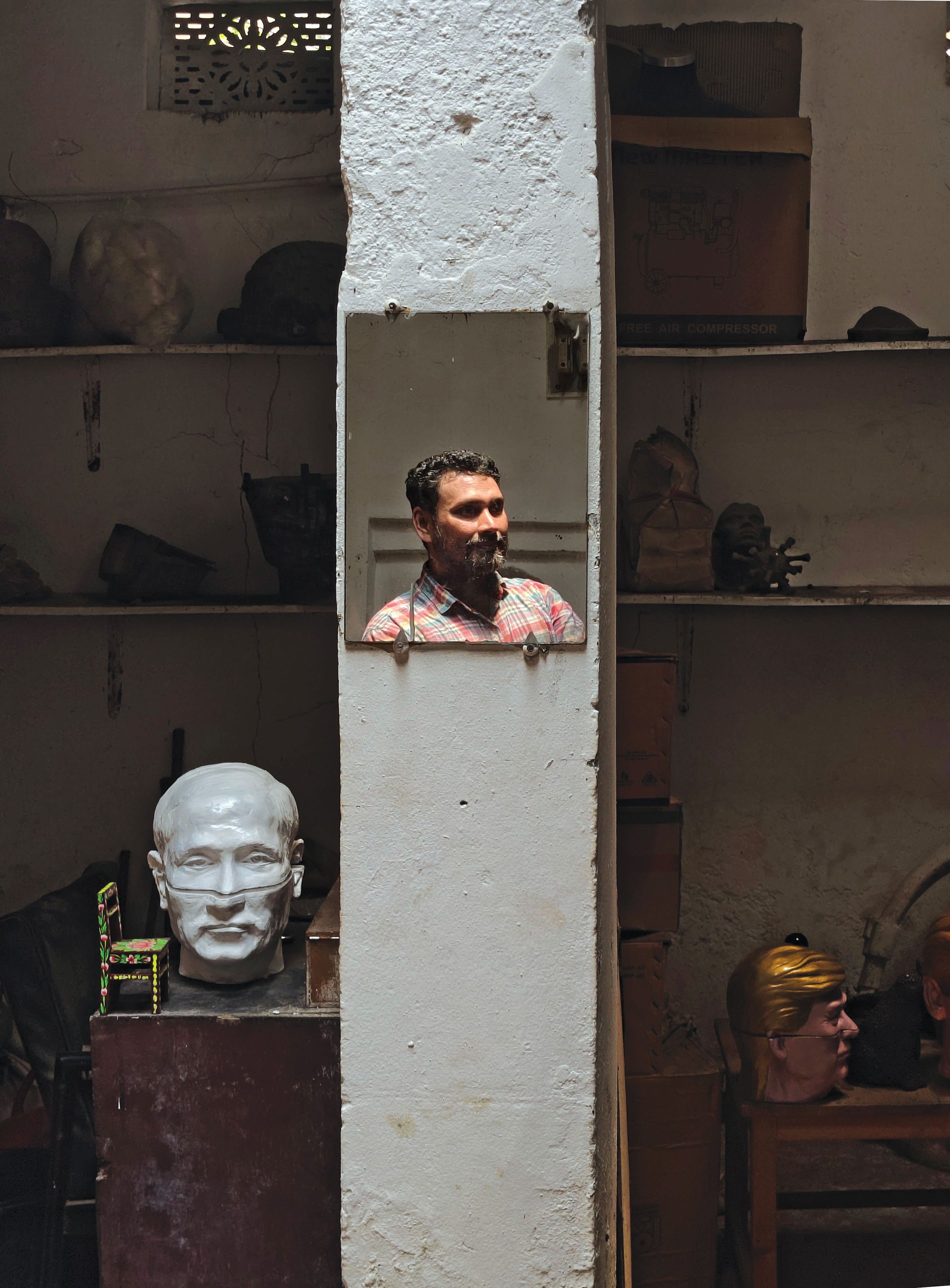

A significant part of Dhaka is Lalbagh and its surrounding areas. One such part is Azimpur—an area deeply embedded in the emotions of the city’s residents, artists, and writers. It carries the weight of Bengal’s history and echoes the sighs of countless lost stories.

Students of Fine Arts, especially those who stayed at Shahnewaz Hall, often roamed the streets of Azimpur. This neighborhood and its adjacent lanes are breeding grounds for diverse materials and creative techniques. When it comes to creating something new, this area holds unmatched value.

Walking down its streets, I often feel swept back into a different time. Memories from the past come rushing in. I become absent-minded, mumbling unfinished thoughts, as if caught in a trance. A weight settles on the chest, pulls me into a contemplative silence.

In this dreamlike setting, a group of sculptors has set up a ‘Vashkor Khana’ (sculpture studio), detached from the calculations and burdens of everyday life. Among them is a sculptor named ‘Ashik’—Aminul Islam Ashik.

One must navigate several winding alleys steeped in history to reach this space. Past the Chapra Mosque of Azimpur and following Sheikh Shaheb Bazar Road, a rusted tin gate appears wedged between towering buildings through twists and narrow turns. Entering through it, you find an open courtyard. On the left stands an old, lime-washed single-story building. As you step inside, the surrounding concrete giants seem to loom over the fragile structure like a predator waiting to consume it.

Plaster peels from the thick walls, exposing jagged bricks—like teeth breaking through gum. The walls feel scorched and blistered. Ashik immerses himself in his practice inside one of these rooms, surrounded by half-finished sculptures and an assortment of materials. His unfinished works seem to wait in queue —longing for the sculptor’s touch to complete their form. Whether they will ever be completed remains uncertain.

I had visited this house once before, for a personal project. Back then, it was Munna Bhai’s workshop, and some other artists used to work in adjacent rooms.

We are living in a time when pursuing sculpture as a practice in Bengal is nothing short of a battle. It’s not an easy path. Sustaining a disciplined artistic life amidst such hostility is akin to fighting on the front lines. Ashik Aminul is one of those front-line fighters.

I first became acquainted with Ashik’s artistic vision when he was selected for the Britto Arts Trust Student Residency Program in 2013. Though we hadn’t spoken much then, Ashik and another selected artist, Sohrab Jahan, joined the program in Nepal alongside two Nepali artists. The residency was hosted by BINDU Art Space (an artist-run space in Kathmandu). To my knowledge, this residency experience helped accelerate Ashik’s artistic journey.

Ashik’s artistic style involves mastery in modeling physical form while emphasizing the process as a vehicle for personal expression. Although primarily a sculptor, Ashik feels comfortable experimenting across different mediums and processes.

His art is driven by concepts and commentary, sometimes dictated by the nature of the materials, and sometimes transforming the medium to serve his narrative. Ashik effortlessly reinterprets traditional media in his own language and integrates unconventional materials.

For example, soft clay becomes a dreamy vessel of emotion shaped by the flow of his hands, and from rigid frameworks, he extracts new imagined structures. At times, molten metal solidifies into a form constructed by his creative vision. These dialogues between the artist and material are deeply personal—silent conversations with the self.

Art is both self-fulfillment and a shared experience for Ashik. It allows him to release his inner pressure, finding calm in his own creation. At other times, he uses his art to pose questions to society—gently, insistently, through form. His works are often narrative-based, reflecting present-day social realities. As a result, his artistic language leans toward descriptive storytelling, even though expressing narrative in three-dimensional form is more challenging than in two dimensions. But it is in this complexity that the artist’s honesty shines.

Times change, artistic trends shift. Yet the true artist remains rooted in his thought and practice—a silent prayer that all beings be happy. Let power politics dissolve, weary soldiers return home, and peace reign.

Written from Krabi Island, Thailand 9 May 2025